Hello, beautiful people! I’m Cole Meyer, and I’m a sophomore planning to join the astrophysics department and pursue certificates in applied and computational mathematics and applications of computing. On campus, I’m involved in everything from student agencies to rocketry club to effective altruism, and am hoping to join the climbing team in the Fall. I also love cooking/baking, keeping my dogs (Duke and Ollie) entertained, running, and spending an unreasonable amount of time making the perfect cup of coffee.

This summer, I’m interning with the ALMA Observatory, a large-scale international scientific collaboration in the form of a 66-antennae radio telescope array located in the Atacama Desert of Chile. The array is quite spectacular; it is the largest radio telescope in the world, and employs astronomers and physicists from the United States, Europe, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Chile.

My work with ALMA revolves around one idea: unexpected antenna “movement”. Let me explain. In order to interpret the radio signals arriving at the array from distant sources, we need to do a calculation that accounts for the distortion of arriving waves. This calculation is based on a number of factors like the water vapor in the atmosphere above the array, various weather attributes (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, pressure, etc.), and a few others. If we do this calculation perfectly, our data should imply that the antennae in the array are completely still. However, since the calculation is incredibly difficult to do accurately, the data seems to be implying that our antennas are moving (which, unless the Earth has a heartbeat, cannot be the case!). So, my work involves investigating the various components of this calculation in the hopes of identifying its shortcomings.

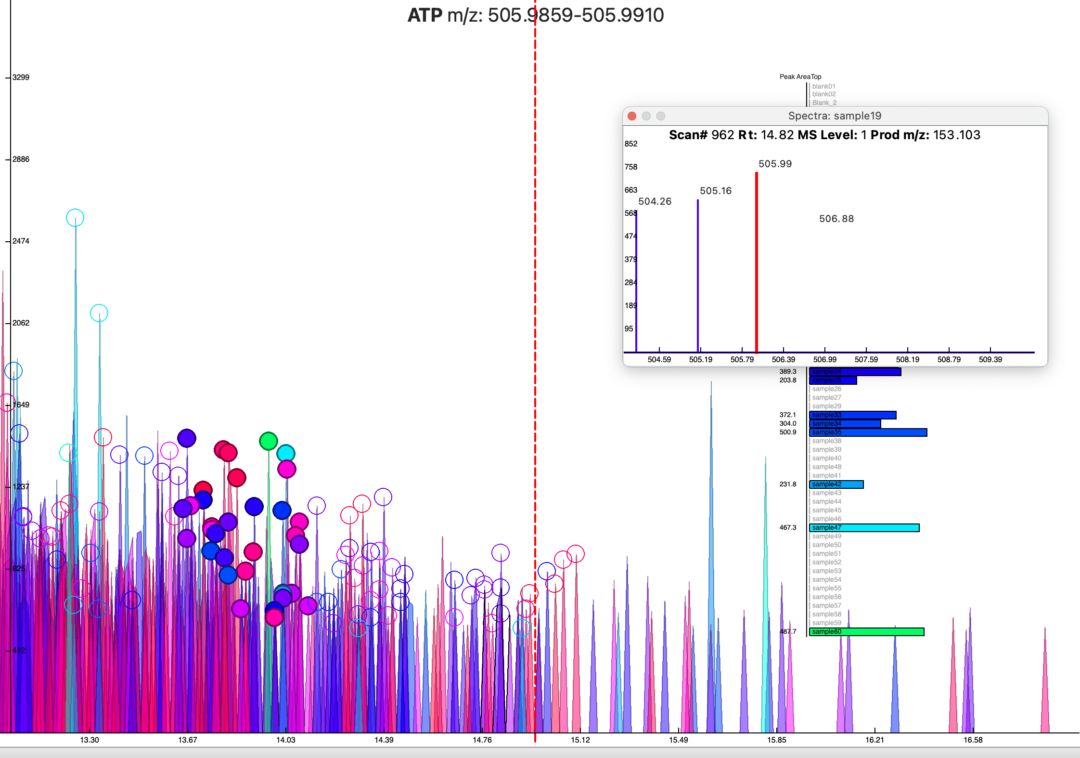

Day-to-day, this investigation manifests itself primarily in the production of lots and lots of plots (coding) that a few other astronomers and I can attempt to interpret for some additional insight. The idea is that, if we plot enough data in enough combinations, eventually something interesting will be revealed to us that we can pursue further.

While this brute-force approach is not ideal by any stretch, it is incredibly valuable to ALMA. The observatory’s calibration accuracy has been suffering as a result of this phenomenon since its inception–numerous groups have attempted to investigate it strategically (with methods far above my head!), but have come up empty-handed. So, for the issue to be resolved, they really needed somebody to take this painstaking approach. My hope is that, upon identification of the issue, we can begin to improve the accuracy of the array so that astronomers all around the world may continue to use this incredible tool to investigate the intricacies of the universe as effectively as possible.